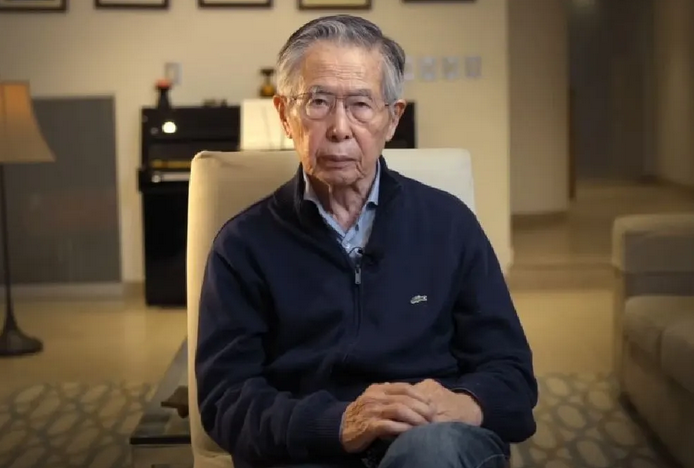

Former President Alberto Fujimori, who died Wednesday at age 86 after a long battle with cancer, is being honored with flags at half-staff on all public buildings and three days of mourning. His coffin will lie in state at the Museum of the Nation until his funeral on Saturday.

As president of Peru from 1990 to 2000, he leaves a conflicted legacy of efficiency and economic success coupled with harsh authoritarian rule, corruption, and human rights abuses.

The divide is evident between his staunch supporters and equally passionate detractors, reflected in today’s headlines: “He Will Live in the Heart of the People,” says the daily Noticia, and “Ex-Dictator Alberto Fujimori Dead” in La República.

Rise to Power

A dark horse in the 1990 general election, his campaign highlighted him as a smiling, down-to-earth man driving a tractor (he was rector of the Agrarian University), known as El Chino, a common nickname in Peru for those of Asian descent. He won 62.32% of the vote against novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, whose Fredemo party promised a neoliberal program to overhaul the economy. At the time, Peru was suffering from government mismanagement, 10 years of internal conflict, and 7,000% inflation.

Early Presidency and Economic Shock

But the Apra party, still influential despite President Alan Garcia’s administration, threatened that rivers of blood would run if Vargas Llosa’s policies were implemented. Fujimori promised he would not apply any shock tactics, and Vargas Llosa lost in the run-off.

But the Apra party, still influential despite President Alan Garcia’s administration, threatened that rivers of blood would run if Vargas Llosa’s policies were implemented. Fujimori promised he would not apply any shock tactics, and Vargas Llosa lost in the run-off.

Fujimori had no real political party, no government experience, and few advisors. Yet, according to former colleagues at the Agrarian University, Fujimori was known for his ability to succeed ruthlessly at any task.

The military approached Fujimori, who then spent several weeks in the army officers club on Av. Salaverry for training, learning about government. The military effectively became co-governor with Fujimori, led by General Nicola di Bari Hermoza, commander-in-chief-of the armed forces.

Fujimori was accompanied by Vladimiro Montesinos, whose return to the officers’ club marked a first since his court martial for treason in 1977. Montesinos, who studied law while in the army prison, earlier helped Fujimori with a real estate tax evasion problem during the campaign.

Montesinos became Fujimori’s closest advisor.

A week after his inauguration, Fujimori’s finance minister, Juan Hurtado Miller, announced a shock economic program on national television — a program very similar to Vargas Llosa’s. The “Fujishock” included a 400% wage increase, but fuel prices rose by 3,040%, electricity by 5,270%, and water by 1,318%. Hurtado Miller ended the address with, “May God help us.”

Although stunned, the country did not see rivers of blood.

Congress, however, obstructed the government’s privatization efforts, slowing progress.

Autogolpe and Constitutional Reform

In April 1992, Fujimori addressed the nation, announcing the dissolution of Congress as troops and armored vehicles fanned out across the capital. The move was widely supported. He also reorganized the judiciary and state institutions, with the military assuming control as part of a long-term strategy known as Plan Verde.

From the beginning, Fujimori governed closely alongside Montesinos, who became his intelligence chief, and General Hermoza.

After dissolving Congress, Fujimori called for elections and a new constitution, which eliminated the Senate, allowed for presidential re-election and implemented reforms that stabilized the economy for the next 30 years.

Capture of Abimael Guzman

In September 1992, Fujimori became a national hero when Shining Path leader Abimael Guzman was captured by a close-knit police investigation unit. The team had, in fact, waited until Fujimori was in the north jungle on a fishing trip and most cabinet and military brass were at meetings outside Lima. Guzman had managed to slip through the team’s net twice before, suspected to have been due to operational leaks.

The capture brought huge relief —thousands had died over the previous 10 years at the hands of Guzman’s followers and the police and military, and only three months earlier, the Tarata bomb in the center of Miraflores had killed 25 people and injured 150. Five of the dead were never identified.

Economic Reforms and Privatization

Fujimori enacted privatization laws. A slate of state-owned businesses — with the exception of Petroperu— went up for sale or concession, including the national airline and railway services. In 1994, Spain’s Telefónica successfully bid for the phone company and changed communications overnight. After years of expensive and hard-to-get landlines, mobile phones were suddenly everywhere, impacting small businesses across the country.

Faced with constant strikes by a powerful public transport union, Fujimori authorized the importation of new and second-hand buses by anyone — private companies or individuals — who wanted to open up new city routes. While the initiative provided a much-needed boost to services, it also introduced the enduring chaos and informality that still define Lima’s transport system today.

Human Rights Abuses and Media Control

With economic recovery came a darker side: human rights abuses continued, and political manipulation intensified.

Fujimori’s government, with Montesinos increasingly in charge, controlled the media. Pre-approved headlines and news stories were delivered to dutiful newspapers, TV and radio stations. Smear campaigns increased against critics, effectively ruining careers. A climate of fear and loyalty to Fujimori pervaded, even spawning a tabloid named El Chino.

Political opponents and business leaders were often blackmailed or threatened, forced to align with the regime’s decisions. The new tax authority Sunat compiled a list of protected tax-payers who favored Fujimori’s decisions, while dissenting companies and individuals faced fines or were shut down for minor infractions. Executives in government institutions were fired if they didn’t toe the line. Even major international advertising agencies were barred from placing ads with blacklisted, non-compliant media outlets.

During the first years of Fujimori’s reign, little or nothing was known of Montesinos’ growing Machiavellian power and influence behind the scenes.

It wasn’t until late into Fujimori’s second term that a leaked video emerged, showing how dozens of high-ranking naval officers were obligated to sign a pledge of allegiance to Montesinos in his presence.

The government also worked with the media that had bank debts or were delinquent in their tax payments, including several newspapers and the TV Channels 2, 4 and 5 (Latina, America and Panamericana). Media owners were regularly given millions of dollars in cash — later released video recordings show media owners receiving the wads of cash from Montesinos — in exchange for broadcasting spoon-fed headlines and news coverage and, in the case of TV, to create raucous programs designed to dumb down the public.

Re-election and Controversial Policies

In 1995, now eligible for re-election under the new Constitution, Fujimori had a strong following and beat former UN Secretary General, Javier Perez de Cuellar. While observers deemed the election result clean, the campaign was rife with disinformation and the communications of Perez de Cuellar and his wife were wire-tapped.

Fujimori’s second term saw an increasingly bold administration, with harsher responses to critics.

A controversial family planning program, backed by international organizations, aimed to curb population growth through voluntary sterilization campaigns. The program was supported by USAID and UNFPA. The health ministry, however, set quotas for health workers, and many poor, illiterate women were misinformed or coerced into sterilization. They faced threats of losing food aid or medicine if they refused the surgery.

Third Term Attempt and Downfall

In 2000, sticking to his Plan Verde 20-30 year strategy, Fujimori sought a legally questionable third term, exploiting a loophole in the constitution he had shaped.

But public unrest over corruption and authoritarianism surged, and Alejandro Toledo, a Stanford-educated economist, emerged as the leading challenger. Fujimori failed to secure the required majority of 50% plus one vote, triggering a run-off election. However, Toledo refused to participate, claiming the results had already been rigged.

Fujimori was sworn in on July 28, despite a massive protest days earlier, where hundreds of thousands from across the country converged on Lima. Not even military blockades on highways and Amazon tributaries could halt the Marcha de los Cuatro Suyos.

The march remained largely peaceful. However, on the day of the inauguration, thugs infiltrated the final demonstration near Congress, setting fire to parts of the Palace of Justice, the ground floor of the Ministry of Education, and a Banco de la Nación building, which was completely engulfed in flames, killing six security guards. Although the government quickly blamed Toledo, investigations later revealed that the arson had been orchestrated by Montesinos.

Fujimori’s third administration lasted barely three months. Freshman congressman Beto Kouri was caught on hidden camera accepting stacks of cash from Montesinos, who placed the money into a paper bag at the spy chief’s headquarters.

This was the first of the infamous Vladivideos, leaked to Toledo supporters by an intelligence insider. The footage revealed Montesinos bribing a wide array of congressional members to ensure they followed directives, with legislators even receiving beepers for instant instructions on how to vote. The Vladivideos also showed Peruvian titans of business and media moguls receiving cash and instructions from Montesinos, who soon went into hiding, and then fled to Panama.

Fujimori also fled the country, ostensibly to join an APEC summit in Brunei, but rerouted his plane to Japan. He sent in a letter of resignation to Congress by fax.

Exile, Arrest, and Conviction

In Japan, Fujimori campaigned as a Japanese citizen for election to the national parliament, but was unsuccessful. Five years later, in 2005, he flew to Chile, via Mexico, intending to make his political comeback in Peru. But he was arrested in Chile and in 2007, Chile’s Supreme Court granted his extradition on seven of 13 charges filed by Peru.

Fujimori was convicted and sentenced in April 2009 to 25 years in prison for human rights abuses. These included the forced kidnappings of journalist Gustavo Gorriti and businessman Samuel Dyer in 1992, as well as for his responsibility in the deaths of 25 people during the La Cantuta and Barrios Altos massacres, carried out by a military death squad.

He became the first Latin American president to be tried and convicted for crimes committed during his presidency, in a trial widely praised by legal scholars for its integrity. Fujimori served 18 years—16 in a Peruvian prison and two under pre-trial arrest in Chile—but never paid the S/ 57 million (USD 13.9 million) in civil damages.

Final Years and Legacy

Fujimori was pardoned in 2017 by President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski on humanitarian grounds but his release was rescinded and he returned to prison — a private suite at the Barbadillo police barracks where former presidents Alejandro Toledo and Pedro del Castillo are being held.

Fujimori was hospitalized on several occasions over the past 10 years or so.

In December 2023, the Constitutional Court ruled that Fujimori be released for health reasons. The Court had ruled his release in March 2022, but this was blocked by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. In December last year, however, the Court refused to acknowledge the IACHR decision.

Despite a grim prognosis, Fujimori was filmed joining the Fujimorist party, Fuerza Popular, in July, with Keiko Fujimori announcing that her father would be the party’s 2026 presidential candidate.

Few of his supporters and detractors seem to be able or even willing to weigh both his achievements and failures. “Today begins Alberto Fujimori’s judgement by history,” said former congresswoman and presidential candidate Lourdes Flores.